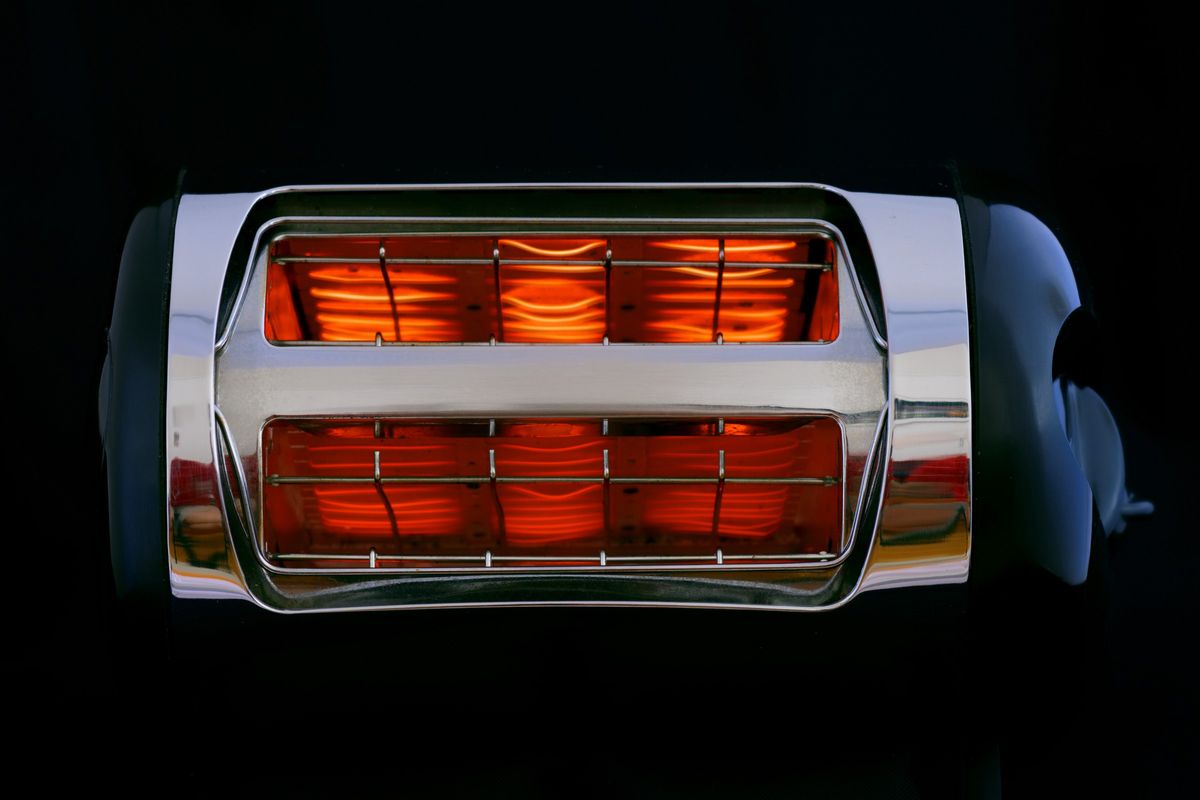

Speeding Up APIs/Apps/Smart Toasters with HTTP Response Caching

Caching is a huge topic, and there’s a lot of different types of caching. No one type of cache is going to suite all needs and cover everything needed to make a performant application, but one type that’s often overlooked is client caching at the HTTP level.

Building a permissions API at work, a user and company UUID are provided. The permissions API fetches the user and company data from another API, and may make a few other calls. The evaluator decides if they can do the thing or not, based on their data, and some rules. ABAC is fun y’all.

Checking one policy could internally generate 3–5 HTTP calls to a handful of dependencies. The client calling permissions (client A) would be waiting for those responses, because permissions (client B) is making a whole bunch of calls.

Client A could be asking to check 10 policies, all of which might request different remote data sources, and the user could belong to multiple companies, all of which need to be looked up too. This could mean 20 HTTP requests are need be made, which is a lot.

We implemented a little Ruby memoization to avoid duplicate requests, but that will not help with multiple Client A calls making similar requests, or the same requests shortly after.

At this point people usually recommend adding some cache logic to the application (application caching), which in Rails looks a bit like this:

Rails.cache.fetch("users/#{uuid}") do

UserAPI.find_user(uuid)

end

If there is nothing in the cache matching that user then it’ll run the block and fetch the thing. That’s handy and all, but how long does that cache entry last?

Forever! Infinity is a long time, so we have to provide a reasonable date.

Rails.cache.fetch("users/#{uuid}", expires_in: 12.hours.from_now) do

UserAPI.find_user(uuid)

end

That’s great and all, but 12 is an arbitrary number plucked out of thin air. Client B is now making up its own rules about resources it doesn’t own…

At the most basic this leads to "My email address is showing up differently in two systems”, but beyond that there may be all sorts of business logic potentially involved with how long data should be cached.

Ignoring those concerns, I still have to litter my codebase with all of this code, wrapping every HTTP call in caching logic that I had to guess at.

Or...

The server can tell the client how long to store things, just as browsers do!

Whenever you go to pretty much any website, the server defines various cache-related headers. These headers are outlined in RFC 7234: HTTP/1.1 Caching and Darrel Miller broke it down in Caching is Hard, Draw Me a Picture.

Expires: Sat, 06 Oct 2018 12:00:00 GMT

This is an example of the most basic cache header, but there are many more.

Your browser will respect these HTTP headers unless it’s told not to (e.g: hard refresh) and that’s how CSS/JS/HTML is cached. Basically the browser will skip the request that response is already in the cache.

When we build systems that call other systems, we often skip out this step, and performance can suffer.

Implementing HTTP Response Caching

Using a single gem, I calmed Client B down substantially. Benchmarking with siege:

siege -c 5 --time=5m --content-type "application/json" -H "Authorization: Token token=snip" https://permission-api.example/endpoint POST { ...not relevant... }

All of a sudden the Permissions API (client B) went from this:

Transactions: 443 hits

Response time: 3.35 secs

Transaction rate: 1.48 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.00 MB/sec

Successful transactions: 443

Failed transactions: 0

Longest transaction: 5.95

Shortest transaction: 0.80

... to this:

Transactions: 5904 hits

Response time: 0.25 secs

Transaction rate: 19.75 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.00 MB/sec

Successful transactions: 5904

Failed transactions: 0

Longest transaction: 1.75

Shortest transaction: 0.12

Boom!

This benchmark is of course fairly artificial due to requesting the same user and membership data thousands of times, but the initial requests are ~800ms (down from ~3.5s) and repeat requests are down to ~200ms (from also 3.5s). This is substantial however you spin it.

This is all done with standard expire-based caching, and not conditional caching. That’s a whole other barrel of fish, which we’re not going to get into here.

I WANT THIS!

Writing all the code to do this would be a big job. Luckily, there are solutions built in pretty much every single language.

Ruby

client = Faraday.new do |builder|

builder.use :http_cache, store: Rails.cache

...

end

plataformatec/faraday-http-cache - a faraday middleware that respects HTTP cache.

PHP

use GuzzleHttp\Client;

use GuzzleHttp\HandlerStack;

use Kevinrob\GuzzleCache\CacheMiddleware;

// Create default HandlerStack

$stack = HandlerStack::create();

// Add this middleware to the top with \`push\`

$stack->push(new CacheMiddleware(), 'cache');

// Initialize the client with the handler option

$client = new Client(['handler' => $stack]);

Kevinrob/guzzle-cache-middleware - A HTTP Cache for Guzzle 6. It's a simple Middleware to be added in the HandlerStack.

Python

import requests

import requests_cache

requests_cache.install_cache('demo_cache')

requests-cache - Persistent cache for requests library.

JavaScript (node)

const http = require('http');

const CacheableRequest = require('cacheable-request');

const cacheableRequest = new CacheableRequest(http.request);

const cacheReq = cacheableRequest('http://example.com', cb);

cacheReq.on('request', req => req.end());

cacheable-request - Wrap native HTTP requests with RFC compliant cache support.

Go

proxy := &httputil.ReverseProxy{

Director: func(r *http.Request) {

},

}

handler := httpcache.NewHandler(httpcache.NewMemoryCache(), proxy)

handler.Shared = true

log.Printf("proxy listening on http://%s", listen)

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(listen, handler))

lox/httpcache - An RFC7234 compliant golang http.Handler for caching HTTP.

On The Other Hand

Not every HTTP GET request is one you want to cache. The middleware will generally do the correct thing so long as the server has declared their intentions well.

Regardless of how well the server declares its cacheability, you may way to store things for longer. Disrespecting the use-by date can have similar effects to ignoring the date on a carton of milk, but if you’re aware of what you’re doing then sometimes ignoring the intentions of the server to persist longer makes sense.

Sometimes its Inefficient

If you are making multiple calls to APIs with large responses to create one composite resource (one local thing made out of multiple remote things) you might not want to cache the calls.

If the client is only using a few fields from each response, caching all of the responses is going to swamp the cache server. File-based cache stores might be slower than making the HTTP call, and Redis or Memcache caches may well run out of space.

Besides, restitching the data from those multiple requests to make the composite resource locally may be too costly on the CPU. In that case absolutely stick to application-level caching the composite resource instead of using the low level HTTP cache. You can use your own rules and logic on expiry, etc. because the composite item is yours.

One final example: if you have data that changes based on the authenticated user, you’ll need to use Vary: Authentication, which basically segments the caches by Authentication header. Two requests that are identical in all ways other than the Authentication header will result in two different cache results.

This can lower cache hit ratios so much it might not be worth worrying about. Depends. Give it a try.

Conventions = Prizes

The cool thing about HTTP caching is that once a server has declared its cacheability, not only can clients leverage that metadata to seamlessly know when to skip requests, but cache proxies can then offer cached responses to requests clients do actually make.

Properly explaining cache proxies is another article in itself, but the topic is outlined in the previous article GraphQL vs REST: Caching.

Caching is a great way to avoid doing slow stuff multiple times. Of course keep working on making things not be slow in the first place, but being able to have servers define their rules and clients automatically follow those rules is a fantastic way to add some stability to your architecture.

The fewer HTTP calls we make, the better our smart toasters will run, and with all that saved energy we’ll stop the ice caps melting! 👍🏼