Organizing your AsyncAPI documents

Written by Fran Méndez and re-posted here with permission.

A recurring question that I get very often is: "how do I organize my AsyncAPI documents?". Also, the related one: "I have two services, a publisher and a consumer, should I define both in the same AsyncAPI document?".

Let’s break down some best practices and tips to avoid ending up in a hell of unmanageable documents.

I’m using the term microservices here because it’s the most common type of distributed architecture that you can find nowadays.

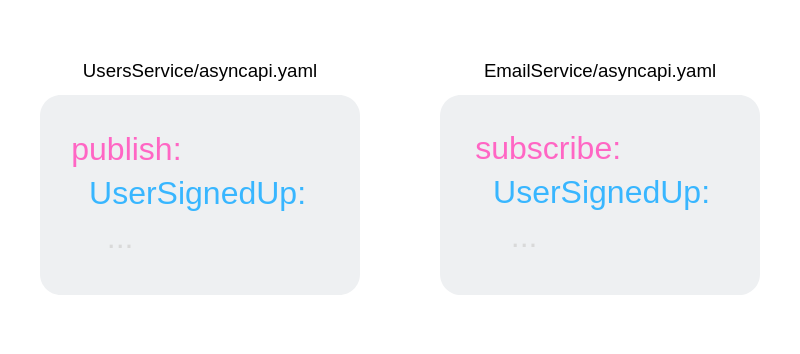

The best practice for organizing AsyncAPI files in your microservices architecture is to have a file per microservice. This way, you end up with multiple independent files that define your application.

One publisher and one subscriber, both sharing the UserSignUp message.

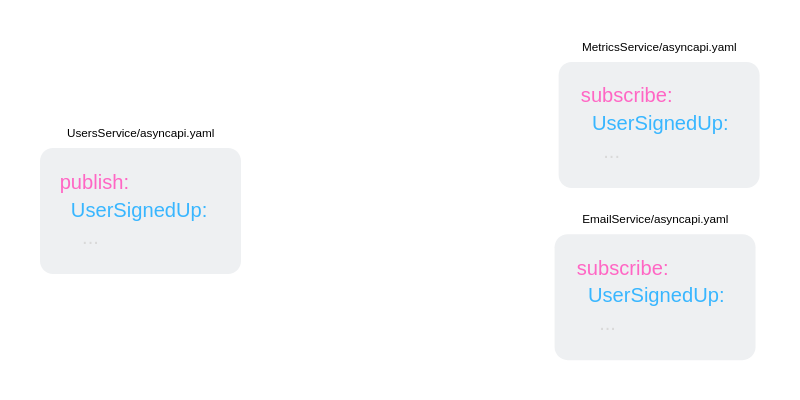

Microservices are meant to do a single thing and to do it well and, very importantly, they must be independently deployable. However, if you have a publisher and multiple consumers, you quickly end up having something like the following:

One publisher and various subscribers. All of them sharing the UserSignUp message.

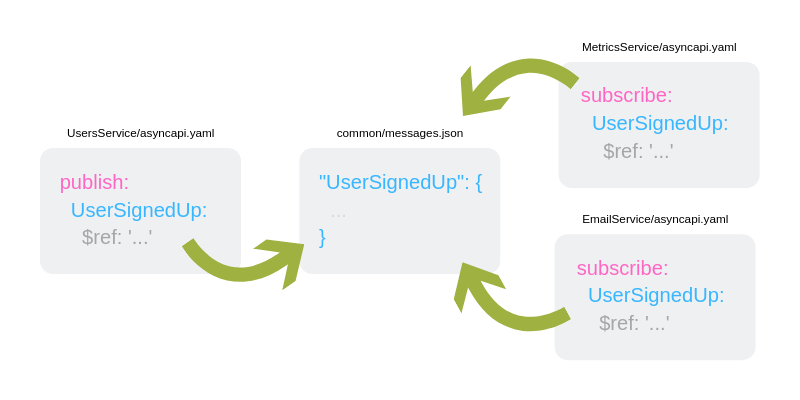

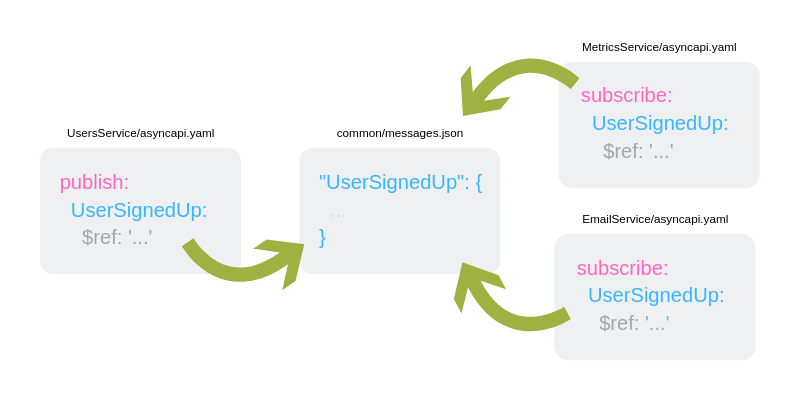

It’s clear there’s a dependency between all of them: the UserSignedUp message. If at some point to want to change it, you’ll have to go through all of the files and change it. It’s a tedious task we want to avoid, so we can make use of the $ref capability of AsyncAPI to simplify things:

The value of $ref should be "common/messages.json#UserSignedUp".

Now, if you have to add something to the UserSignedUp message, it’s just a matter of changing one file. Depending on your setup, you may have to restart your services to get the new definition. However, as simple and straightforward as it may seem, you must take care not to introduce breaking changes in the message definition. Otherwise, you’ll have inconsistent states while some services got the new message definition and some didn’t yet. Here comes the importance of versioning your messages, but that makes for another blog post alone.

Since microservices tend to be small in scope, most probably their AsyncAPI document will not be very extensive too. And I found out this is one of the reasons people tend to re-use the same file for many services. They think the file is very small and because the publisher and the subscriber share the same message, why not putting everything there? It’s tempting at first, but the reason why you should avoid doing this is that you lose context and semantics, and it causes problems:

- If a single document contains publish and subscribe for the same channel (topic), how do you know which one is defining what your application does?

- Since your document may contain many channels, how do you know if your application is publishing or subscribing to each channel or just a subset of them? That itself causes more problems, for instance, when you want to generate the documentation for a single service but you have a single file defining your whole architecture and thus a single documentation page describing all the services without any clue which one is doing what.

An AsyncAPI file is meant to define the behavior of a single application. You can obviously break the rules and use it to define the whole architecture but expect all sorts of problems to appear because you’re using a hammer to saw a piece of wood. The same way you don’t use a single OpenAPI (Swagger) file to define many of your REST APIs, you shouldn’t use a single AsyncAPI document to define many of your message-driven APIs.

Say, for instance, you have a WebSockets API and front-end application using it. The paradigm is very similar to the one we’re used to with HTTP APIs, with the subtle difference that the communication is full duplex, i.e., the client can send and receive messages over the same channel, at any time.

This case is not very different from the microservices one. If you think about it, we can look at it as a small distributed architecture, where you only have two services: the client and the server. So the recommended best practice is to follow the same approach and have one document for each of the applications — one for the server and another for the client or front-end.

I want to reinforce the point that an AsyncAPI file is meant to define the behavior of a single application. Keep this always in mind, and everything will make sense to you.

Happy coding! ✌️

AsyncAPI is an open source project running on donations so please, consider donating. 🙌