Streaming Data with REST APIs

Are you forcing API clients to wait for every single byte of massive JSON collections to be sent from the server before letting them render data that's ready already?

It's exciting times in the world of API design, with OpenAPI v3.2 finally showing that a version after 3.1 was possible. Amongst various improvements it's bringing "JSON Streaming" as a new feature, which begs the question: WTF is JSON Streaming?

HTTP Streaming

Let's look at streaming in HTTP and the browser, because whenever we're talking about HTTP/REST APIs, there's usually not much difference.

Images can be streamed, and that's what has that top-to-bottom effect with large images on slow connections.

Streaming is not just for images, the browser isn't waiting for 100% of HTML to load before it decides to render anything either.

Once the browser receives the first chunk of data, it can begin parsing the information received. Parsing is the step the browser takes to turn the data it receives over the network into the DOM and CSSOM, which is used by the renderer to paint a page to the screen. – Source: MDN, How Browsers Work.

The server sends chunks of data which are more manageable, and as soon as a client knows what to do with however many chunks it has so far it can do whatever with them. In the case of anything visual that'll be rendering as much as it can as it gets more chunks in, but this also works nicely for data.

Can HTTP/REST API responses be streamed?

Absolutely! Imagine a HTTP API was responding with a CSV file. We can stream that CSV content record by record.

When a client knows how to handle chunks of a stream, it will. Curl does a great job of showing how a client could handle it by putting one line out to the terminal as each line comes in, but you could imagine each line being processed and saved into a database instead.

How does that stream get sent though? What magic am I doing on the server-side of things?! Nothing as exciting as you might think.

import express from "express";

const app = express();

app.get("/tickets.csv", async (req, res) => {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/csv; charset=utf-8");

res.setHeader("Transfer-Encoding", "chunked");

// Write CSV header immediately

res.write("TrainNumber,Departure,Destination,Price\n");

const tickets = [

{ train: "ICE 123", from: "Berlin", to: "Munich", price: 79.90 },

{ train: "TGV 456", from: "Paris", to: "Lyon", price: 49.50 },

{ train: "EC 789", from: "Zurich", to: "Milan", price: 59.00 }

];

let i = 0;

const interval = setInterval(() => {

if (i < tickets.length) {

const t = tickets[i];

res.write(`${t.train},${t.from},${t.to},${t.price}\n`);

i++;

} else {

clearInterval(interval);

res.end();

}

}, 1000); // 1 row per second for demo

});

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`Server running at http://localhost:3000`);

});

All its doing is writing lines as it goes, instead of writing everything all at once.

Also this is not some special streaming endpoint that is massively different from the normal CSV response. In this example I've simply upgraded the existing CSV endpoint with special sauce added via a few extra headers.

The key bits in this Node/Express.js example are res.setHeader("Transfer-Encoding", "chunked"); and the loop outputting res.write(...) calls instead of instead of building up a big array and converting it all to JSON all at once.

In any language that has the concept of "generators" or "yielding" instead of working with big arrays and returning it all, this can be a huge memory reduction. We simply don't need to think about N things at once, only ever one thing at a time. This removes a lot of strain on memory of both the server and client.

If a client does not understand the stream or doesn't want to mess with that, it will simply wait until it has received the entire response before continuing offering graceful fallbacks for this functionality.

Instead of using the CLI you might use something like fetch() and the built-in reader, which you can learn more about here.

What about streaming JSON

You can imagine a problem here. If you tried to stream JSON line by line you'd get a lot of invalid syntax errors, because there would be an opening { or [ then a bunch of other bits and bobs, and no ending } or ]. This syntax error would throw out any existing JSON parsers or validators so people would be stuck coding up awkward homegrown solutions. Some people have tried to build and popularize their homegrown solutions, but it's pretty awkward, and as usual we have been rescued by standards.

Of course there cannot be just one standard, there need to be a few slightly different ones. You can use JSONL, NDJSON, or RFC 7464: JSON Text Sequences and they're basically the same thing.

All these approaches are simply known as "JSON Streaming", and the goal is to modify JSON just a little bit to bring those streaming benefits to a HTTP API.

This is how a JSONL or NDJSON response might look in an API.

{"train":"ICE 123","from":"Berlin","to":"Munich","price":79.9}

{"train":"TGV 456","from":"Paris","to":"Lyon","price":49.5}

{"train":"EC 789","from":"Zurich","to":"Milan","price":59}

At first you might think that this is just JSON but... enhance.

It's not an array of objects. This is a series of JSON objects, each on their own new line. This solves the streaming syntax issue, by making each and every line a completely valid object.

Any request to /tickets.jsonl will respond with this stream of JSON objects on new lines. Any programming language can handle this easily, and core/standard JSON tooling can be used to handle each line one at a time.

Streams can serve a set collection of data, or they can run for as long as the server or client keeps the connection open. This is handy when the response is thousands of things, or potentially infinite things, but definitely super handy when collections are massive.

When to Stream?

When would you use JSON streaming in a REST versus something more common like pagination?

Let's look at a few use-cases:

- Some folks are using it for AI agents to help people buy eggs for 10x the usual price for some reason.

- The Twitter team are using it so the Nazi community can filter through the firehose of fascist shitposts to recruit new members in real-time.

- I'm using it to help reforest the U.K. by helping Protect Earth handle survival surveys and data collection, showing tens of thousands of pins for each tree we've planted onto our various site maps around the country. Doing this without crashing out the server or the browser was important as we consistently work on larger and larger projects.

Some of these use-cases are more helpful to the world than others, but they all fit with streaming better than pagination.

Pagination is more about showing some content to a client which is going to decide if it wants to grab more data or not. Perhaps the client (or end-user) found what it wanted on the first page and doesn't need to go through everything else. It would have been a misuse to use pagination for "do you want to see some more trees on this map" even if I could get the UI to do that.

Streaming is more helpful when all the data is needed but it's not "all or nothing", allowing people to do what they can but with a reasonable exception they will need a whole bunch more. It's also helpful when you want to keep sending infinite updates without polling, WebHooks, or WebSockets, because they might be overkill for something like getting some updates to a single payment attempt in the moment.

Once again there's a standard for that, called Server Sent Events, and it works really well inside HTTP/REST APIs for sending updates. This might sound a bit like the Subscription feature in GraphQL, but as with everything in GraphQL it's inspired by a substantially more useful HTTP standard/convention that came out at least a decade before.

That's two pretty different use cases for streaming, but it's not a single feature that has a single use, it's a fundamental rethink to assumptions about API design that assume we always have to respond once, and only once.

API Design Considerations

In the example of the CSV response we automatically streamed the response and let clients decide if they wanted to read it as a stream or not.

With the JSON streaming thats a little different, because this is not simply JSON in "Stream mode". For example, if you started sending JSONL (multiple JSON objects over multiple lines) to a client which expected actual JSON, you would have a whole lot of syntax errors and grumpy customers.

To avoid anyone making this mistake copying sample code I popped everything onto their own endpoints like GET /tickets.jsonl, but there's no need to work like that.

You could amend an existing GET /tickets to respond differently to a client sending Accept: application/json or Accept: application/jsonl, giving this choice to the client and using the Accept header for exactly what it's for.

Is it RESTful to stream data?

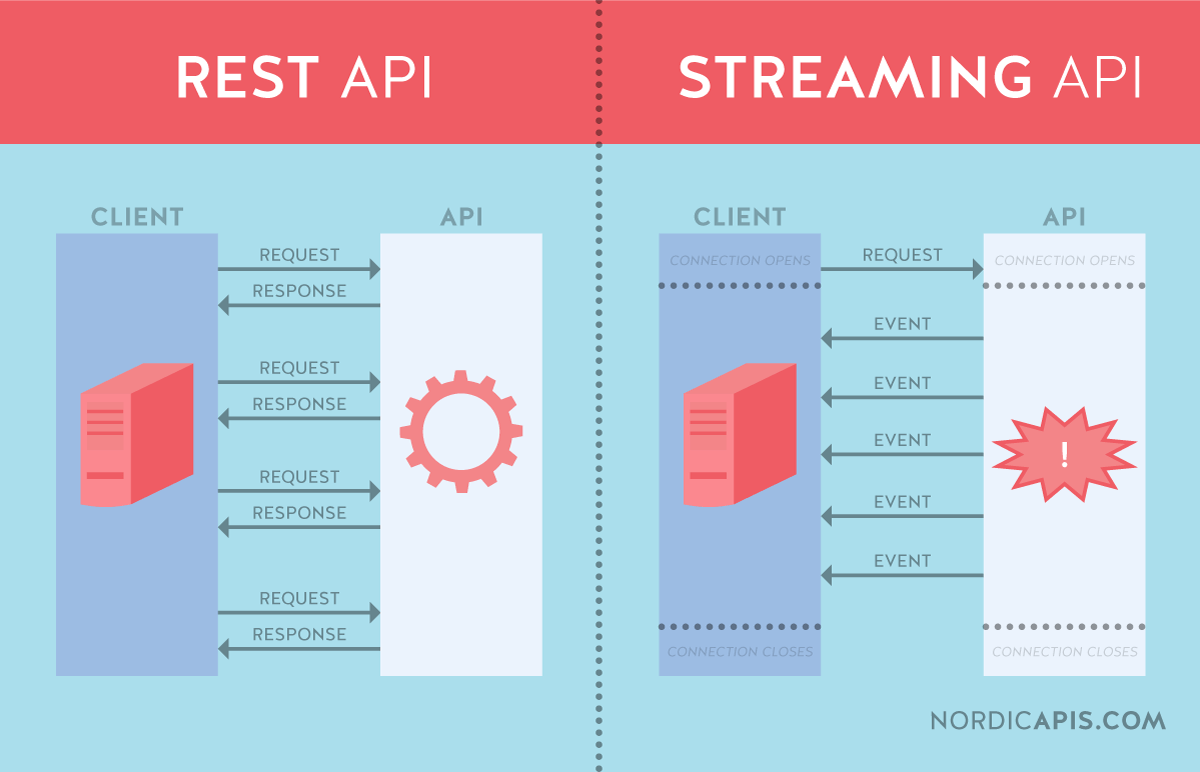

According to Nordic APIs you can't stream data or events in REST, because "Streaming APIs are almost the exact opposite of the REST ethos." Thankfully they're wrong about that.

There is nothing at all in REST that says an API can only have one response to a request, or that the response has to be sent all at once. Some people have an outdated understanding on REST APIs constraint about using the uniform interface of the web, which is really about not inventing proprietary nonsense. That doesn't mean we're forced to ignore new HTTP functionality as it rolls out. By this logic REST APIs would be stuck in some state of Amish-like time-based technology cut-off, where only HTTP functionality from circa 2000 allowed and everything newer was strictly forbidden.

Some of this is a semantic issue, and Nordic APIs are incorrectly setting their definition of "Streaming APIs" == "Event-driven APIs". At least I presume, as they're mentioning "RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, or Azure Event Hub, ... [and] event streaming platforms include Apache Kafka, Apache Flink, and Apache Beam."

That is misleading. Those are types of Asynchronous APIs, and async APIs are a subset of event-driven APIs. These may co-exist on the same architecture as REST APIs handling different pieces of the puzzle. Sometimes a REST API will be there to answer questions about the current state because a REST API is a state-machine over HTTP, and the event-driven APIs will be running around updating or commanding each other, pushing those REST resources through various states in various workflows as they go.

But a REST API can also stream, that's definitely not something only Event-driven or Async APIs can do.

Let's reuse the diagram from Nordic API as its a perfect diagram for explaining how REST APIs can stream despite it saying that they can't.

If the REST API is streaming events then this diagram is already just fine. If it's streaming data would could rename "Event" to "Chunk" or "Item", then once again this diagram is now perfectly describing how REST APIs can handle streaming responses to a request.

Event-driven and message-driven APIs are fundamentally rather different, and nobody should be trying to crowbar JSON streaming into REST APIs when what they really needed was a full blown event-based architecture, but by the same token we need to stop pretending people need to roll out complex systems like Kafka or even WebSockets when the only thing that was needed was an extra HTTP header and a different content type.

Describing JSON Streaming with OpenAPI

Nothing about JSON Streaming is particularly new. Data scientists and GIS communities have been usig it for ages, with AI hype types getting a use out of it too, but it's being brought to the API community especially thanks to the upcomming OpenAPI v3.2 release adding the JSON streaming support.

If you'd like to learn more about how JSON streaming looks in OpenAPI then check out this handy guide written for Bump.sh.

Keeping up with HTTP

It always feels like API designers ignore a lot of lessons from the wider Internet. We are still designing bloated API responses with all loosely related secondary and tertiary data all thwacked in together to reduce number of HTTP calls. This was a concept akin to Image Sprites which fell out of popularity once HTTP/2 took over in ~2015, but API developers will just not let the concept go.

With

Similarly getting people to enable HTTP caching on their APIs (generally just by headers and probably reusing CDNs they already pass through!) has become a full time job for years. People instead focus on the response times of requests that didn't need to be made, instead of learning to skip making requests that didn't need to be made.

If we take these more learnings from the larger HTTP world, and combine them with streaming certain datasets instead of defaulting to pagination (a.k.a polling with a cursor), or pushing events instead of forcing polling, then APIs can become a whole lot more efficient.

Efficiency reduces costs, reduces hardware requirements, lowers carbon emissions of the software, and helps companies do less carbon accounting. Learn more about how this all links up with the Green Software Practioner course. It's free.

Cover Photo for this article by Jachan DeVol on Unsplash