Taking a Timeout from Poor Performance

In a system-oriented architecture, it is crucial to communicate with other

systems. In an ideal world each service knows enough information to satisfy its

clients, but often there are unfortunate requirements for data to be fetched on

the fly. Broker patterns, proxies, etc., or even just a remote procedure being

triggered synchronously, like confirming an email has been sent successfully.

All of these things take time. Frontend applications (desktop, web, iOS,

Android, etc.) talk to services, and services talk to other services. This chain

of calls can stack up, as service A calls service B, unaware that system is

calling service C and D… So long as A, B, C and D are functioning normally, the

frontend application can hope to get a response from service A within a

"reasonable time”, but if B, C or D are having a bad time, it can cause a domino

effect that takes out a large chunk of your architecture, and the ripple effects

result in a slow experience for the end users.

Slow applications can cost you a lot of money. A Kissmetrics

survey suggests that every

1s slower a page loads, 7% fewer conversions will occur. This article explains

how you can make your applications remain performant when upstream dependencies

are not, using timeouts and retries.

Other People’s Problems

You own service A, and are making calls to service B. What happens when service

B has a bad day, and instead of responding within the usual ~350ms, it starts to

take 10 seconds? Do you want to wait 10 seconds for that response?

What about if service B is fine, but C is taking 20s and D is taking 25s? Are

you happy to wait 45 seconds for the response from B?

What about two minutes?! 😱

When a server is under load, it can do some pretty wild stuff, and not all

servers know to give up. Even fewer applications know when to give up, and those

that do will take a while to do it.

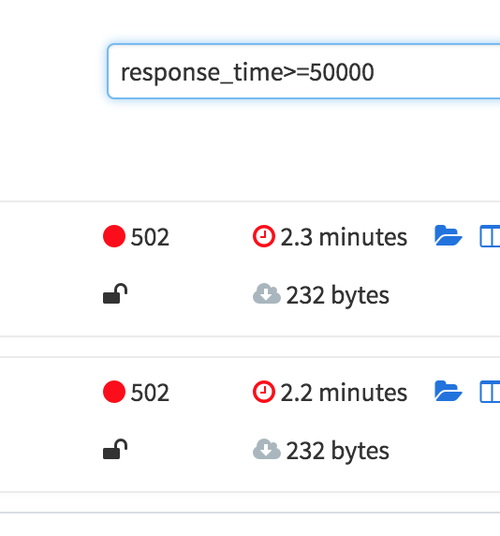

For example, if service B is on Heroku, we can be confident the request is not

going to last for more than 30 seconds. Heroku’s router has a policy:

applications get 30 seconds to send the first byte, and if that doesn’t happen

then the request gets dropped.

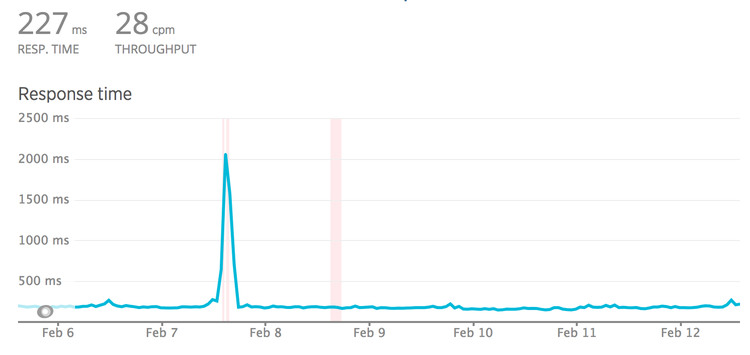

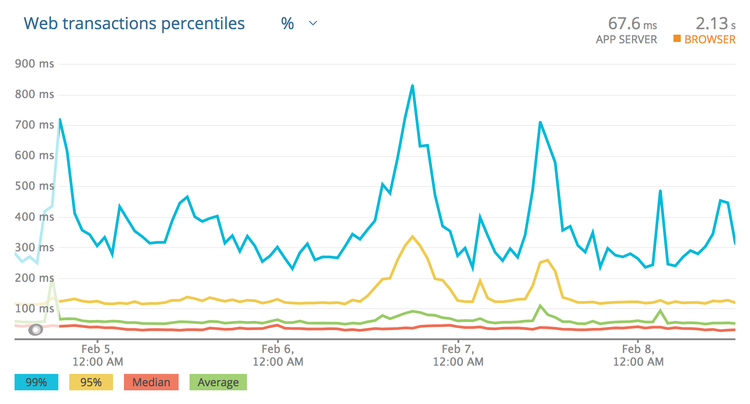

Quite often in monitoring systems like NewRelic or CA APM, you will see things

like this:

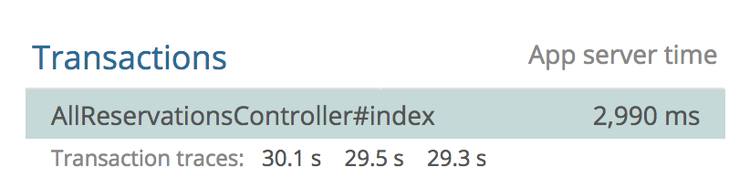

This controller has an average response time of 2.9s, but the slow ones are

floating right around that 30s mark. The Heroku Chop saves the caller from being

stuck there indefinitely, but this behavior is not widespread. Other web servers

with different policies will hang forever.

For this reason, never presume any service is going to respond as fast as it

usually does. Even if that team’s developers are super confident. Even if it

autoscales. Even if it’s built in Scala. If you don’t set timeouts, other

people’s problems become your problems.

So, how can we prevent this from happening?

Set Timeouts in the HTTP Client

HTTP clients are usually generic, and out of the box will wait indefinitely

for a response. Luckily any HTTP client worth its salt will allow you to

configure timeouts.

For Ruby users, the HTTP client

Faraday might look like this:

conn = Faraday.new('http://example.com');

conn.get do |req|

req.url '/search'

req.options.timeout = 5 # open/read timeout in seconds

req.options.open_timeout = 2 # connection open timeout in seconds

end

For PHP, Guzzle does this:

$client->request('GET', '/delay/5', ['timeout' => 5]);

There are two types of timeout that a lot of HTTP clients use:

- Open (Connection) Timeout

- Read Timeout

An open timeout asks: how long do you want to wait around to see if this

server is actually accepting requests. That can mean many things but often means

a server is too busy to take a request (there are no available workers

processing the traffic). It also depends in part on expected network latency. If

you are making an HTTP call to another service in the same data center, the

latency is going to be a few milliseconds, but going to another continent takes

time.

The read timeout is how long you want to spend reading data from the server

once the connection is open. It’s common for this to be set higher, as waiting

for a server to generate an answer (run queries, fetch data, serialize it, etc.)

should take longer than opening the connection.

When you see the term "timeout” on its own (not an open timeout or a read

timeout) that usually means the total timeout.

Faraday takes timeout = 5 and

open_timeout = 2 to mean "I demand the server marks the connection as open

within 2 seconds, then regardless of how long that took, it only has 5 seconds

to finish responding.”

Some must die, so that others may live

Any time spent waiting for a request that may never come is time that could be

spent doing something useful. When the HTTP call is coming from a background

worker, that’s a worker blocked from processing other jobs. Depending on how you

have your background workers configured, the same threads might be shared for

multiple jobs. If Job X is stuck for 30s waiting for this server that’s failing,

Job Y and Job Z will not be processed or will be processed incredibly slowly.

That same principle applies when the HTTP call is coming from a web thread.

That’s a web thread that could have been handling other requests! For example,

POST /payment_attempts is making an HTTP call in the thread which is usually

super quick, but unfortunately, some service it talks to is now blocking it for

30s. Other endpoints usually respond in 100ms, and they will continue to respond

so long as there are threads available in the various workers… but if the

performance issues for the dependency continue, every time a user hits POST /payment_attempts, another thread becomes unavailable for that 30s.

Let’s do a bit of math. For each thread that gets stuck, given that thread is

stuck for 30s, and most requests go through in 100ms, that’s 3000 potential

requests not being handled. 3000 requests not being handled because of a

single endpoint. There will continue to be fewer and fewer available workers,

and given enough traffic to that payment endpoint, there might be zero available

workers left to work on any the traffic to any other endpoints.

Setting that timeout to 10s would result in the processing of 2000 more

successful requests.

As a general advice: please do try and avoid making requests from the web

thread, put them in background jobs whenever possible. Sometimes it is

unavoidable, but please go to painstaking efforts to try and avoid doing it.

Making timeouts happen early is much more important than getting a fast failure.

The most important benefit of failing fast is to give other workers the chance

to work.

If the server is a third party company, you might have a service-level agreement

stating: "Our API will always respond in 150ms”. Great, set it to 150ms (and

retry on failure if the thing is important.)

If the service is in-house, then try to get access to NewRelic, CA APM or

whatever monitoring tool is being used. Looking at the response times, you can

get an idea of what should be acceptable. Be careful though, do not look only

at the average.

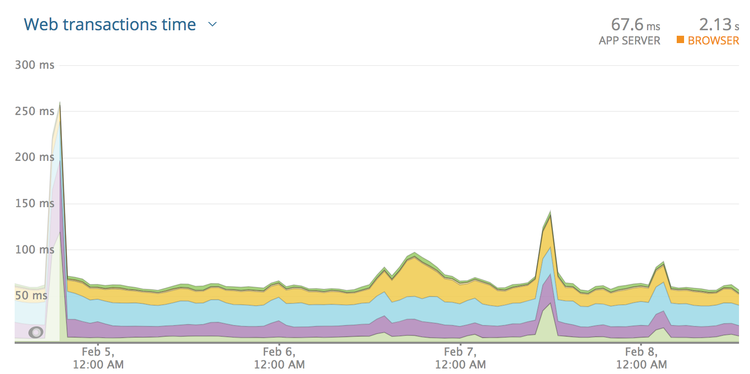

Looking at this graph may lead you to think 300ms is an appropriate timeout.

Seems fair right? The biggest spike there is 250ms and so round it up a bit and

let’s go for 300ms?

Nope! These are averages, and averages are going to be far far lower than the

slowest transactions. Click the drop-down and find "Web transaction

percentiles.”

That is a more honest representation. Most of the responses are 30–50ms, and the

average is usually sub 100ms. That said, under high load this service starts

to stutter a bit, and these peaks can lead to responses coming in around

850ms! Clicking around to show the slowest traces will show a handful of

requests over the last few weeks coming in at 2s, 3.4s, and another at 5s!

Those are ridiculous, and looking at the error rate we can see that those

requests didn’t even succeed. Whatever happens, setting the timeout low enough

to cut those off is something we want to do, so far I’m thinking about 1s. If

the transactions are failing anyway, there is no point waiting.

Next: if the call is being made from a background worker, that 99 percentile of

850ms may well be acceptable. Background workers are usually in less of a rush,

so go with 1s and off you go. Keep an eye on things and trim that down if your

jobs continue to back up, but that’s probably good enough.

Backup plan: retry

If it’s a web process… well, 2s+ is certainly no good, especially seeing as it

might fail anyway. Waiting around for this unstable transaction to complete is

as much of a good plan as skydiving with just the one chute. Let’s create a

backup plan using retries.

So we have this special web application that absolutely has to have this web

request to Service B in the thread. We know this endpoint generally responds in

35–100ms and on a bad day it can take anywhere from 300–850. We do not want to

wait around for anything over 1s as its unlikely to even respond, but we don’t

want this endpoint to take more than 1s…

Here’s a plan: set the timeout to 400ms, add a retry after 50ms, then if the

first attempt is taking a while boom, it’ll give up and try again!

conn = Faraday.new('http://example.com');

conn.post('/payment_attempts', { ... }) do |req|

conn.options.timeout = 0.4

conn.request :retry, max: 1, interval: 0.05

end

There is potential for trouble here, as the second and first attempts might end

up in a race condition. The interval there will hopefully give the database long

enough to notice the first response was successful, meaning the 2nd request will

fail and say "already paid” or something intelligent, which can be inspected and

potentially treated as a success by the client.

Anyway, (400 * 2) + 50 = 950, with another 50ms for whatever other random gumf

is happening in the application, should mean that we come in at under 1 second!

This is a good place to be in. You have 2x the chance of success, and you’re

setting tight controls to avoid service B messing your own application up.

An important note for Ruby users: you are already using

retries

on idempotent requests, and you probably had no idea. It’s wild that NetHTTP

does this by default.

Next Step: Circuit Breakers

Timeouts are a great way to avoid unexpected hangs from slowing a service down

too much, and retries are a great solution to having another when that

unexpected problem happens. These two concepts are both reactive, and as such

can be improved with the addition of a third proactive concept: circuit

breakers.

Circuit breakers are just a few lines of code, maybe using something like Redis

to maintain counters of failures and their timestamps. With each failure to a

service (or a particular endpoint on that service), the client increments a

failure counter and compares it to a certain threshold. Maybe that threshold is

10 failures in 1 minute, or for higher volume systems maybe 5 failures in a

second.

So in our example, Service A might notice that service B is down after the 10th

error in 1 second, and at that point it opens the circuit breaker, meaning it

completely stops making calls to that system. This will decrease the load on

downstream services (B, C, and D), giving them a chance to recover. This also

avoids the "running out of threads” issue we discussed previously. Even with

service A giving up after 1s, that’s still 1s that thread could have spent

handling other requests.

What to do when a circuit breaker is open? It depends on the feature the circuit

breaker is wrapping.

- Immediately respond with an error, letting the user know the required system is down, and to try again later

- Have a secondary system kick in that handles things in a different way

- Divert traffic to a cluster of servers elsewhere

- Record information about the attempt and have customer services reach out

That’s only a quick intro to circuit breakers, so head over to see Martin

Fowler explain circuit breakers in

depth if you want more

information on the topic.

Envoy is also a great example of a tool that can

handle a lot of this for you at a network level, instead of asking you to code

it up yourself and the application level.

Hopefully, these tips will help keep your applications ticking along smoothly

and avoid a domino effect taking out a giant chunk of your architecture.