The Many Amazing Uses of JSON Schema: Client-side Validation

These days type systems are all the rage in APIs, and with gRPC and GraphQL fans

touting their baked in systems. REST fans have a few options for type systems,

but JSON Schema seems to be powering forwards as the primary candidate.

JSON Schema is metadata for JSON, which can be used for a whole bunch of things.

We've written about how JSON Schema can really simplify contract

testing,

how JSON Schema can add non-invasive hypermedia controls to existing

APIs,

and - seeing as JSON Schema is mostly compatible with

OpenAPI - it can be used to generate meaningful and beautiful human-readable

documentation

too!

Now let's talk about validating API requests. Again, this is another chunk taken

from the book. Download the latest version from

Leanpub to get this

chapter and more (existing customers should have had an email about it.)

Whenever an API client attempts an operation (creating a REST resource,

triggering an RPC procedure, etc.) there are usually some validation rules to

consider. For example, the name field is required and and cannot be longer

than 20 characters long, email must be a valid email address, the date field

should be a valid ISO 8601 date, and

either the home phone or mobile phone field must be entered to send a text

message, etc.

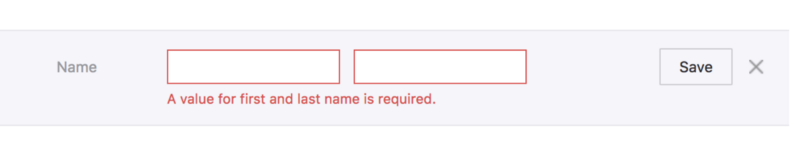

There are two locations in which these rules can live, the server and the

client. Client-side validation is incredibly important, as it provides immediate

visual feedback to the user. Depending on the UI/UX of the client application,

this might come in the form of making invalid boxes red, scrolling the user to

the problem, showing basic alert boxes, or disabling the submit button until the

local data looks good.

To create this functionality, a common approach is to reproduce server-side

validation in the client-side. This should be avoided at all costs.

It is awfully common for client developers to read the API documentation, take

note of prominent validation rules, then write a bunch of code to handle those

rules on their own end. If their code considers the data valid, it will pass it

all onto the server on some event (probably on submit) and hopefully the server

will agree.

This seems to make sense at first, as frontend applications want immediate

feedback on input without having to ask the server about validity. Unfortunately

this approach does not scale particularly well, and cannot handle even the

smallest evolution of functionality. Rules can be added, removed or changed for

the API as the business requirements change, and clients struggle to keep up to

date. Arguably the API development team should not be randomly changing things,

but change always happens in some form. The varying versioning strategies for

APIs

aside, even extremely cautious API developers can introduce unexpectedly

breaking change when it comes to validation.

The most simple example would be the above mentioned name field, with a max

length of 20 characters. Months later, requirements come in from the business to

increase the max length to 40, and the API rolls out that change. (Still not

how names

work,

but Twitter just did this.)

The API developers have a chat, and decide that making validation rules more

lenient cannot be considered breaking, as all previous requests will still

function. So they deploy the change with a max length of 40 characters, and one

client-app deploys an update to match, increasing the validation to 40. Despite

various client applications still having the hardcoded max length at 20

characters, everyone feels pretty happy about this.

One user jumps on this chance for a long name, going well over the 20 character

limit. Later on the iOS application, they try to edit another field on the same

form, but notice their name has been truncated to 20 characters as the input

field will not take any more than that. Confused, they grab their friends phone

and try it out there. The Android application does something a little different:

the full 40 characters are populated into the form, but client-side validation

is showing an error when the form is submitted. The user profile cannot be

updated at all on this application without the user truncating their name…

Well built APIs generally offer a copy of their contracts in a programmatically

accessible format. The idea is that validation rules should be written down

somewhere, and not just inside the backend code. If the validation rules can be

seen by API clients, clients are going to be far more robust, and not break on

tiny validation changes.

JSON Schema to the Rescue

JSON Schema is very simple; point out which fields might exist, which are

required or optional, what data format they use. Other validation rules can be

added on top of that basic premise, along with human-readable information. The

metadata lives in .json files, which might look a bit like this:

{

"$id": "http://example.com/schemas/user.json",

"type": "object",

"definitions": {},

"$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft-07/schema#",

"properties": {

"name": {

"title": "Name",

"type": "string",

"description": "Users full name supporting unicode but no emojis.",

"maxLength": 20

},

"email": {

"title": "Email",

"description": "Like a postal address but for computers.",

"type": "string",

"format": "email"

},

"date_of_birth": {

"title": "Date Of Birth",

"type": "string",

"description": "Date of uses birth in the one and only date standard: ISO 8601.",

"format": "date",

"example": "1990–12–28"

}

},

"required": ["name"]

}

There is quite a lot of stuff here, but most of it should make sense to the

human eye without too much guesswork. We are listing properties by name, giving

them a data type, setting up maxLength for the name according to the example

earlier, and putting human-readable descriptions in there too. Also some

examples have been thrown in for giggles.

The one bit that probably needs more explaining is the $schema key, which is

pointing to the draft version of JSON Schema in use. Knowing which draft you are

validating against is important, as a JSON Schema file written for Draft 07

cannot be validated with a Draft 06 validator, or lower. Luckily most JSON

Schema tools keep up fairly well, and JSON Schema is not madly changing crap at

random.

Anyway, back to it: An example of a valid instance for that .json schema file

might look like this.

{

"name": "Lucrezia Nethersole",

"email": "l.nethersole@hotmail.com",

"date_of_birth": "2007–01–23"

}

To try playing around with this, head over to

jsonschemavalidator.net and paste those in.

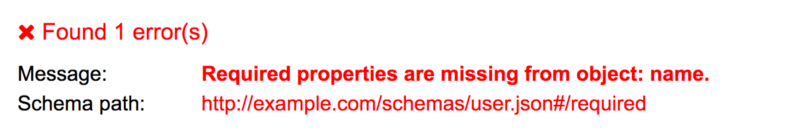

Removing the name field triggers an error as we have "required": ["name"] in

there.

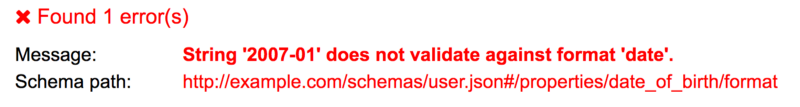

Another validation rule could be triggered if you enter date of birth in an

incorrect format.

Conceptually that probably makes enough sense, but how to actually

programmatically get this done? The JSON Schema .json files are usually made

available somewhere in a HTTP Link header with a rel of "describedby". Link: <http://example.com/schemas/user.json#>; rel="describedby". This might look a

bit off to those not used to Link headers, but this is how a lot of links are

handled these days. The one difficulty here is parsing the value, which can be

done with some extremely awful regex, or with a

RFC5988 compliant link parser — like

parse-link-header for

JavaScript.

Once a API client has the schema URL they can download the file. This involves

simply making a GET request to the URL provided. Fear not about performance,

these are usually stored on CDNs, like S3 with CloudFlare in front of it. They

are also likely to have cache headers set, so make sure your HTTP client knows

how to handle that.

Learn about HTTP caching for clients.

Triggering validation rules on a random website is one thing, but learning how

to do that with code is going to be far more useful. For JavaScript a module

called ajv is fairly popular, so install that

with a simple yarn add ajv@6, then shove it in a JavaScript file. This code is

available on the new books GitHub

Repo.

const Ajv = require('ajv');

const ajv = new Ajv();

// Fetch the JSON content, pretending it was downloaded from a URL

const userSchema = require('./cached-schema.json')

// Make a little helper for validating

function validate(schema, data) {

return ajv.validate(schema, data)

? true : ajv.errors;

}

// Pretend we've submitted a form

const input = {

name: "Lucrezia Nethersole",

email: "l.nethersole@hotmail.com",

registered\_date: "2007-01-23T23:01:32Z"

}

// Is the whole input valid?

console.log('valid', validate(userSchema, input)) // true

// Ok screw up validation...

input['email'] = 123

console.log('fail', validate(userSchema, input)) // [ { keyword: 'type', dataPath: '.email', ...

For the sake of keeping the example short, the actual JSON Schema has been

"downloaded" from

http://example.com/schemas/user.json and

put into a local file. This is not quite how you would normally do things, and

it will become clear why in a moment.

A validation() function is created to wrap the validation logic in a simple

helper, then we move on to pretending we have some input. The input would

realistically probably be pulled from a form or another dynamic source, so use

your imagination there. Finally onto the meat, calling the validation, and

triggering errors.

Calling this script should show the first validation to succeed, and the second

should fail with an array of errors.

$ node ./1-simple.js

true

[ { keyword: 'type',

dataPath: '.email',

schemaPath: '#/properties/email/type',

params: { type: 'string' },

message: 'should be string' } ]

At first this may seem like a pile of unusable gibberish, but it is actually

incredibly useful. How? The dataPath by default uses JavaScript property

access notation, so you can easily write a bit of code that figures out the

input.email was the problem. That said, JSON

Pointers might be a better idea. A much

larger example, again available on Github, will show how JSON Pointers can be

used to create dynamic errors.

Sadly a lot of this example is going to be specific to AJV, but the concepts

should translate to any JSON Schema validator out there.

const Ajv = require('ajv');

const ajv = new Ajv({ jsonPointers: true });

const pointer = require('json-pointer');

const userSchema = require('./cached-schema.json')

function validate(schema, data) {

return ajv.validate(schema, data)

? [] : ajv.errors;

}

function buildHumanErrors(errors) {

return errors.map(function(error) {

if (error.params.missingProperty) {

const property = pointer.get(userSchema, '/properties/' + error.params.missingProperty);

return property.title + ' is a required field';

}

const property = pointer.get(userSchema, '/properties' + error.dataPath);

if (error.keyword == 'format' && property.example) {

return property.title + ' is in an invalid format, e.g: ' + property.example;

}

return property.title + ' ' + error.message;

});

}

The important things to note in this example are the new Ajv({ jsonPointers: true }); property, which makes dataPath return a JSON Path instead of dot

notation stuff. Then we use that pointer to look into the schema objects (using

the json-pointer npm package), and

find the relevant property object. From there we now have access to the human

readable title, and we can build out some human readable errors based off of the

various properties returned. This code might be a little odd looking, but we

support a few types of error quite nicely. Consider the following inputs.

[

{ },

{ name: "Lucrezia Nethersole", email: "not-an-email" },

{ name: "Lucrezia Nethersole", date_of_birth: 'n/a' },

{ name: "Lucrezia Nethersole Has Many Many Names" }

].forEach(function(input) {

console.log(

buildHumanErrors(validate(userSchema, input))

);

});

These inputs give us a whole bunch of useful human errors back, that can be

placed into our UI to explain to users that stuff is no good.

$ node 2-useful-errors.js

[ 'Name is a required field' ]

[ 'Email should match format "email"' ]

[ 'Date Of Birth is in an invalid format, e.g: 1990–12–28' ]

[ 'Name should NOT be longer than 20 characters' ]

The errors we built from the JSON Schema using the properties that exist can get

really intelligent depending on how good the schema files are, and how many edge

cases you cover. Putting the examples in is a really nice little touch, and

makes a lot more sense to folks reading the messages than just saying the rather

vague statement "it should be a date".

If you were to instead find a way to tie these back to the DOM, you could update

your forms with visual updates as discussed earlier: making invalid boxes red,

scroll the user to the problem, show basic alert boxes, or disable the submit

button until the local data looks good!

What about Validation Hell?

Earlier validation hell was mentioned, and JSON Schema is supposed to avoid it.

But how? The API client now has this JSON Schema file locally, and if the server

changes… how does it know? This sample code storing the schema in the repo along

with the source code, which — generally speaking — is a pretty bad idea, only

done for simplicity of the example.

Put very simply, if the API developers change the schema file to have a

maxLength of 40, any client should then get that change the next time they

request the schema file, meaning things are not out of sync.

Almost

That is a fluffy simplicity which has a few real-world caveats to explain…

Consider schema can be found on the HTTP response like this:

Link: <http://example.com/schemas/user.json#>; rel="describedby"

This URL is not versioned, which suggests that it might change. This is…

possibly ok, as long as they have not set a long cache expiry. If a client

application is respecting cache headers, and the schema file has cache headers,

then your application could suffer from validation hell for the duration of that

expiry.

If the cache is only set to something short like 5 minutes, and the change is

only a minor one, that honestly might not be too bad. The whole "multiple

devices being used to try to make profile changes and getting clobbered by a

maxLength change" scenario we have been discussing actually is not ideal when

you need developers to rush in and fix it, but not so bad if it'll fix itself

after a few minutes.

Some APIs version their schema files, and as such new versions should be

published as a new URL.

Link: <http://example.com/schemas/v1.0.0/user.json#>; rel="describedby"

When a minor change is released like the maxLength one, API developers may

well release another version.

Link: <http://example.com/schemas/v1.0.1/user.json#>; rel="describedby"

So long as URLs are not hardcoded in your application, and the URL is being read

from the response (taken from wherever the API provides the link: body or link

header), then the change of URL will automatically cause your application to

fetch the new schema, allowing your application to notice the new validation

essentially immediately.

This is yet another amazing thing JSON Schema can do for your HTTP APIs.

Keep an eye out for more articles showing amazing uses of JSON Schema, such as

dynamic form generation with tools like React JSON Schema

Form.