Understanding RPC, REST and GraphQL

Every API in the world is following some sort of paradigm, whether it knows it or not. They will fall under RPC, REST, or a "query language."

Even if you are confident you understand the difference, do yourself a favor and read them anyway. About 99% of people get this wrong, so you can be in the top 1% with a quick read.

Remote Procedure Call (RPC)

RPC is the earliest, simplest form of API interaction. It is about executing a block of code on another server, and when implemented in HTTP or AMQP it can become a Web API. There is a method and some arguments, and that is pretty much it. Think of it like calling a function in JavaScript, taking a method name and arguments.

For example:

POST /sayHello HTTP/1.1

HOST: api.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"name": "Racey McRacerson"}

In JavaScript, we would do the same by defining a function, and later we’d call it elsewhere:

/* Signature */

function sayHello(name) {

// ...

}

/* Usage */

sayHello("Racey McRacerson");

The idea is the same. An API is built by defining public methods; then, the methods are called with arguments. RPC is just a bunch of functions, but in the context of an HTTP API, that entails putting the method in the URL and the arguments in the query string or body.

When used for CRUD, RPC is just a case of sending up and down data fields, which is fine, but one downside is that the client is entirely in charge of pretty much everything. The client must know which methods (endpoints) to hit at what time, in order to construct its own workflow out of otherwise naive and non-descriptive endpoints.

RPC is merely a concept, but that concept has a lot of specifications, all of which have concrete implementations:

XML-RPC and JSON-RPC are not used all that much other than by a minority of entrenched fanatics, but SOAP is still kicking around for a lot of financial services and corporate systems like Salesforce.

XML-RPC was problematic, because ensuring data types of XML payloads is tough. In XML, a lot of things are just strings, which JSON does improve, but has trouble differentiating different data formats like integers and decimals.

You need to layer metadata on top in order to describe things such as which fields correspond to which data types. This became part of the basis for SOAP, which used XML Schema and a Web Services Description Language (WSDL) to explain what went where and what it contained.

This metadata is essentially what most science teachers drill into you from a young age: "label your units!" The sort of thing that stops people paying $100 for something that should have been $1 but was just marked as "price: 100" which was meant to be cents… It is also worth pointing out if your "distance" field is metric or imperial, to avoid bad math crashing your billion dollar satellite into Mars.

A modern RPC implementation is gRPC, which can easily be considered modern (and drastically better) SOAP. It uses a data format called ProtoBuff, which requires a schema as well as the data instance, much like the WSDL in SOAP.

GRPC focuses on making single interactions as quick as possible, thanks to HTTP/2, and the fact that Protobuff packs down smaller than JSON, but JSON can also be used easily enough.

Representational State Transfer (REST)

REST is a network paradigm described by Roy Fielding in a dissertation in 2000. REST is all about a client-server relationship, where server-side data are made available through representations of data in simple formats. This format is usually JSON or XML but could be anything.

These representations portray data from various sources as simple "resources", or "collections" of resources, which are then potentially modifiable with actions and relationships being made discoverable via a concept known as hypermedia controls (HATEOAS).

Hypermedia is fundamental to REST, and is essentially just the concept of providing "next available actions", which could be related data, or in the example of an "Invoice" resource, it might be a link to a "Payment Attempts" collection so that the client can attempt paying the invoice.

These actions are just links, but the idea is the client knows that an invoice is payable by the presence of a "pay" link, and if that link is not there it should not show that option to the end user.

{

"data"": {

"type": "invoice",

"id": "093b941d",

"attributes": {

"created_at": "2017–06–15 12:31:01Z",

"sent_at": "2017–06–15 12:34:29Z",

"paid_at": "2017–06–16 09:05:00Z",

"status": "published"

}

},

"links": {

"pay": "https://api.acme.com/invoices/093b941d/payment_attempts"

}

}

This is quite different to RPC. Imagine the two approaches were humans answering the phones for a doctors office:

Client: Hi, I would like to speak to Dr Watson, is he there?

RPC: No. *click*

*Client calls back*

Client: I checked his calendar, and it looks like he is off for the day. I would like to visit another doctor, and it looks like Dr Jones is available at 3pm, can I see her then?

RPC: Yes

The burden of knowing what to do is entirely on the client. It needs to know all the data, come to the appropriate conclusion itself, then has to figure out what to do next. REST however presents you with the next available options:

Client: Hi, I would like to speak to Dr Watson, is he there?

REST: Doctor Watson is not currently in the office, he’ll be back tomorrow, but you have a few options. If it’s not urgent you could leave a message and I’ll get it to him tomorrow, or I can book you with another doctor, would you like to hear who is available today?

Client: Yes, please let me know who is there!

REST: Doctors Smith and Jones, here are links to their profiles.

Client: Ok, Doctor Jones looks like my sort of Doctor, I would like to see them, let’s make that appointment.

REST: Appointment created, here’s a link to the appointment details.

REST provided all of the relevant information with the response, and the client was able to pick through the options to resolve the situation. Of course REST would needed to know to follow the "alternative_doctors": "https://api.example.com/available_doctors?available_at=2017-01-01 03:00:00 GMT" link, but that is far less of a burden on the client than forcing it to check the calendar itself, seek for availability, etc.

This centralization of state into the server has benefits for systems with multiple different clients who offer similar workflows. Instead of distributing all the logic, checking data fields, showing lists of "Actions", etc. around various clients — who might come to different conclusions — REST keeps it all in one place.

Other than hypermedia (the most powerful yet most ignored aspect of REST) there are a few other requirements for a system to be a REST API:

- REST must be stateless: not persisting sessions between requests

- Responses should declare cacheablility: helps your API scale if clients respect the rules

- REST focuses on uniformity: if you’re using HTTP you should utilize HTTP features whenever possible, instead of inventing conventions

The goal of these constraints is to make the REST architecture help APIs last for decades, which is almost impossible to do without these concepts.

REST also does not require the use of schema metadata, which many API developers hated in SOAP. For a long time nobody was building REST APIs with schema, but these days it is far more common thanks to JSON Schema.

JSON Schema is inspired by XML Schema — but not functionally identical — and is one of the most important things to happen to HTTP APIs in years, and will be mentioned a lot in further articles.

Unfortunately, REST become a marketing buzzword for most of 2006–2014. It became a metric of quality that developers would aspire to, fail to understand, then label as REST anyway, so most systems saying they’re REST are little more than RPC with HTTP verbs and pretty URLs. As such, you might not get cacheability provided, it might have a bunch of wacky conventions, and there might not be any links for you to use to discover next available actions. These APIs are jokingly called REST_ish_ by people aware of the difference.

On the flip side, a REST API can be used in an RPC fashion if you as the client developer chose to ignore the links. It is not advisable of course, but it is possible.

A huge source of confusion for people with REST is that they do not understand "all the extra faffing about", such as hypermedia controls and HTTP caching. They do not see the point, and many consider RPC to be the almighty. To them, it is all about executing the remote code as fast possible, but REST (which can still absolutely be performant) focuses far more on longevity and reduced client-coupling.

REST can theoretically work in any transportation protocol that provides it the ability to fulfill the constraints, but no transportation protocol other than HTTP has the functionality. To fit REST into AMQP you would need to define hypermedia controls somehow (potentially an array of messages you could call next), a standard for declaring cacheability of the AMQP messages, etc., and create a lot of tooling that does not exist. Basically REST is too powerful for other existing transportation protocols, so it is generally implemented in HTTP.

REST has no specification which is what leads to some of this confusion, nor does it have concrete implementations. That said, there are two large popular specifications which provide a whole lot of standardization for REST APIs that chose to use them:

If the API advertises itself as using these, there is a chance it is a good one. Find a OData client or a JSON-API client in your programming language to save yourself some work. Otherwise go at it yourself with a plain-old HTTP client and you should be ok with a little bit of elbow grease.

GraphQL

Listing GraphQL as a direct comparison to these other two concepts is a little odd, as GraphQL is essentially RPC, with a lot of good ideas from the REST/HTTP community tacked in. Still, it is one of the fastest growing API ecosystems out there, mostly due to some of the confusion outlined above.

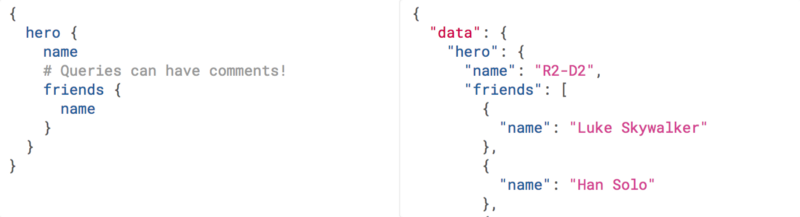

GraphQL is basically RPC with a default procedure providing a query language, a little like SQL — if that is something you are familiar with. You ask for specific resources and specific fields, and it will return that data in the response.

It has Mutations for creates, updates, deletes, etc. and again they are exactly RPC.

GraphQL has many fantastic features and benefits, which are all bundled in one package, with a nice marketing site. If you are trying to learn how to make calls to a GraphQL API, the Learn GraphQL documentation will help, and their site has a bunch of other resources.

Seeing as GraphQL was built by Facebook, who had previously built a REST_ish_ API, they’re familiar with various REST/HTTP API concepts. Many of those existing concepts were used as inspiration for GraphQL functionality, or carbon copied straight into GraphQL. Sadly a few of the most powerful REST concepts were completely ignored.

The backstory to GraphQL, is an interesting one. Facebook has experimented with various different approaches to sharing all their data between apps over the years; remember FQL? Executing SQL-like syntax over a GET endpoint was a bit odd.

GET /fql?q=SELECT%2Buid2%2BFROM%2Bfriend%2BWHERE%2Buid1%3Dme()&access\_token=…

Facebook got a bit fed up with having a REST_ish_ approach to get data, and then having the FQL approach for more targeted queries as well, as they both require different code. As such, GraphQL was created as a middle-ground between endpoint-based APIs and FQL, the latter being an approach most API developers would never consider — or want.

In the end, they developed this RPC-style query language system, to ignore most of the transportation layer, meaning they had full control over the concepts. Endpoints are gone, resources declaring their own cacheability is gone, the concept of the uniform interface (as REST defines it) is obliterated, which has the supposed benefit of making GraphQL so incredibly simple it could fit into AMQP or any other transportation protocol.

The main selling point of GraphQL is that it defaults to providing the very smallest response from an API, as you are requesting only the specific bits of data that you want, which minimizes the Content Download portion of the HTTP request.

It also reduces the number of HTTP requests necessary to retrieve data for multiple resources, known as the "HTTP N+1 Problem" that has been a problem for API developers through the lifetime of HTTP/1.1, but thankfully was solved quite nicely in HTTP/2.

The rest of the chapter, and the rest of the book, will be talking about various pros and cons of these approaches, such as how HTTP caching really suffers in GraphQL compared to other REST/RESTish approaches, how Representing State can be tough, and plenty of other things.

All this in Build APIs You Won’t Hate: Second Edition, currently available for pre-order with the early chapters available for download.

Update 2018–06–01: With this article only covering the technical differences, some folks thought it was about trying to establish which is "the best", instead of trying to be a helpful resource in getting folks thinking about how these different paradigms work. For help picking the right paradigm for any give task, check out Picking the right Paradigm.