Creating Good API Errors in REST, GraphQL and gRPC

Dealing with the Happy Path™ in an API is pretty easy: When a client asks for a

resource, show them the resource. When they trigger a procedure, let them know

if it was triggered OK, and maybe if it completed without a problem.

What to do when something doesn’t go according to plan? Well, that can be

tricky.

HTTP status codes are part of the picture, they can define a

category of issue, but they are never going to explain the whole story.

Two examples from a carpooling application which had a "simulated savings"

endpoint, to let folks know how much they might save picking up a passenger on

their daily commute:

This error let the client know the coordinates were too close together, meaning

it is not even worth driving let alone trying to pick anyone else up.

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

{

"errors" : [{

"code" : 20002,

"title" : "There are no savings for this user."

}]

}

This carpool driver is trying to create a trip from Colombia to Paris.

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

{

"errors" : [{

"code" : 20010,

"title" : "Invalid geopoints for possible trip."

}]

}

This is often touted as a failing of the HTTP status code concept, but it was

never intended to cover every single possible application specific error

message. Think of HTTP status codes like an exception. In Ruby you might get a

ArgumentError or LoadError exception which gives you a pretty good hint as to

what the issue is, but there is also data specific to the instance of that

failure that helps with fixing the situation.

Programming languages do not just give you the exception name, they give you

instance information too.

> require "nonsense"

LoadError (cannot load such file -- nonsense)

Errors in HTTP APIs are pretty similar to exceptions: they can tell the client

what is going on, and combine a bunch of useful metadata to help both the client

and the server solve problems. This is often in the response body, using JSON or

whatever data format the API generally uses.

Error Objects

A well designed API error will have at the very least:

-

A 4xx or 5xx status code depending on the situation

-

A human readable short summary: Cannot checkout with an empty shopping cart

-

A human readable message: It looks like you have tried to check out but there is nothing in your…

-

An application-specific error code relating to the problem:

ERRCARTEMPTY -

Links to a documentation page or knowledge base where a client or user of the client can figure out what to do next

This will help humans and machines to figure out what is happening. Missing out

the error code means clients need to implement substring matching, which is

awful for everyone, and turns contents of the error message into part of the

agree contract. Imagine a text-change breaking integration with multiple unknown

clients! 😳

This used to happen with Facebook and their rather bad Graph API, where any

issue with an access token would return type: OAuthException, regardless of the

type of issue. If it was an expired token which needed a refresh, or if it was

just total nonsense, you would get the same type, and a different string.

{

"error": {

"type": "OAuthException",

"message": "Session has expired at unix time 1385243766. The current unix time is 1385848532."

}

}

Without getting too much into Authentication at this point, there are times

where the client would want to take different actions for different errors. For

example, when an access token was previously good but expires, the client wants

to suggest the user try logging in again, or reconnecting their Facebook

account. When the token is just nonsense (a totally invalid token) then a

different action needs to be taken.

These days Facebook have a far more robust error object in their Graph API, with

error codes and even "sub-codes", so the client developer has enough information

to react programmatically to various errors.

An improved version of that error message, with an error code and a link

{

"error": {

"message": "Message describing the error",

"type": "OAuthException",

"code": 190,

"error_subcode": 460,

"error_user_title": "A title",

"error_user_msg": "A message",

"fbtrace_id": "EJplcsCHuLu"

}

}

They explain the structure of the error object in their documentation.

- message: A human-readable description of the error.

- code: An error code. Common values are listed below, along with common recovery tactics.

- error_subcode: Additional information about the error. Common values are listed below.

- error_user_msg: The message to display to the user. The language of the message is based on the locale of the API request.

- error_user_title: The title of the dialog, if shown. The language of the message is based on the locale of the API request.

- fbtrace_id: Internal support identifier. When reporting a bug related to a Graph API call, include the fbtrace_id to help us find log data for debugging.

Know Your Audience

Making errors be useful for client users (not just client developers) can be a

powerful thing. Clients can build their interface around the expectation that a

link in an error will help their users out, without needing to know specifically

what the actual error is.

Whenever possible try to avoid creating an API error that you would not want to

show to a user. Often a client will create a filter that checks for certain

errors to do something, and anything left can be thrown up as a generic error

box with the message in it.

Clients doing this help future proof their application. For example, if a new

validation rule pops up they might not have their UI code written to check for

that, but an ugly alert box can pop up with instructions to the user and maybe

that is better than the application just being completely unusable.

Another useful thing to do is put a link for more information.

Add a href/link/url property to your error object.

{

"error": {

...

"href": "http://example.org/docs/errors/#ERR-01234"

}

}

In some instances maybe this more information link points to a blog post or some documentation which explains that the user should update their application, or take some other action to resolve the situation, or email somebody, or reset their password. 👍

The Trouble with Custom Error Formats

Everyone starts off building APIs with their own error format. It usually starts off as just a string.

{

"error": "A thing went really wrong"

}

Then somebody points out it would be nice to have application codes, and new versions of the API (or some different APIs built in the same architecture) start using a slightly modified format.

{

"error": {

"code": "100110",

"message": "A thing went really wrong"

}

}

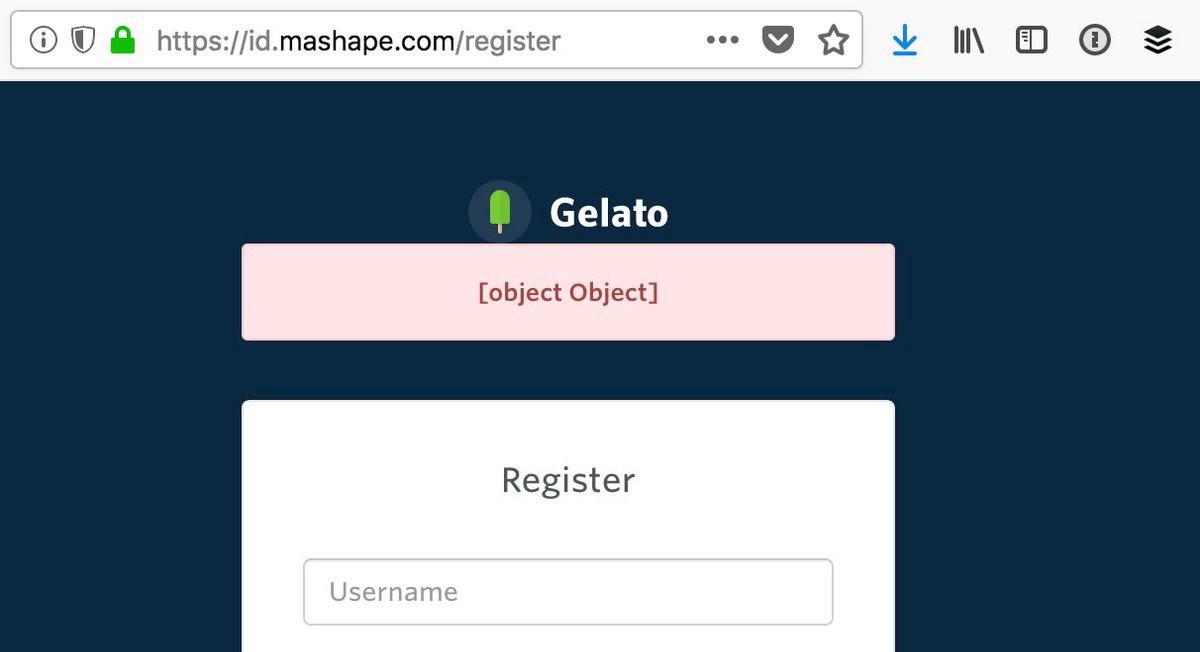

Guess what happens when a client is expecting the first example of a single

string, but ends up getting that second example of an object?

These errors happened at my previous job all the time, because every one of the

50 APIs had a totally different error format, some had multiple different error

formats in different API versions (v2 and v3 would have different error

formats), and you would be expected to hit

both!

I remember writing a bunch of code that would check for various properties, if

error is a string, if error is an object, if error is an object containing foo,

if error is an object containing bar….

Standard Error Formats

There are two common standards out there for API errors which you should

consider using for your next API, or maybe even consider adding to your existing

APIs.

Problem Details for HTTP APIs

Problem Details for HTTP APIs (RFC 7807) is a brilliant standard from Mark Nottingham, Erik Wilde, released through the IETF.

This document defines a "problem detail" as a way to carry machine-readable details of errors in a HTTP response to avoid the need to define new error response formats for HTTP APIs.

— Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)

The goal of this RFC is to give a standard structure for errors in HTTP APIs that use JSON (application/problem+json) or XML (application/problem+xml).

HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

Content-Type: application/problem+json

Content-Language: en

{

"type": "https://example.com/probs/out-of-credit",

"title": "You do not have enough credit.",

"detail": "Your current balance is 30, but that costs 50.",

"instance": "/account/12345/msgs/abc",

"balance": 30,

"accounts": ["/account/12345", "/account/67890"]

}

This example from the RFC shows the user was forbidden from taking that action, because the balance did not have enough credit. 403 would not have conveyed that (it could have meant the user was banned, or all sorts of things) but there is text, and there is a type, which is just an error code in the form of a URL.

Note that this requires each of the sub-problems to be similar enough to use the same HTTP status code. If they do not, the 207 (Multi- Status) [RFC4918] code could be used to encapsulate multiple status messages.

A problem details object can have the following members:

- type (string) — A URI reference [RFC3986] that identifies the problem type. This specification encourages that, when dereferenced, it provide human-readable documentation for the problem type (e.g., using HTML [W3C.REC-html5–20141028]). When this member is not present, its value is assumed to be abou:blank".

- title (string) — A short, human-readable summary of the problem type. It SHOULD NOT change from occurrence to occurrence of the problem, except for purposes of localization (e.g., using proactive content negotiation; see [RFC7231], Section 3.4).

- status (number) — The HTTP status code ([RFC7231], Section 6) generated by the origin server for this occurrence of the problem.

- detail (string) — A human-readable explanation specific to this occurrence of the problem.

- instance (string) — A URI reference that identifies the specific occurrence of the problem. It may or may not yield further information if dereferenced.

Remembering all of this might be a little tricky, and asking every API developer to go read and memorize an RFC might not be particularly successful. As with most things, there are implementations that can be slotted into place for languages and web application frameworks to make the whole thing easier.

-

Java: problem & problem-spring-web

JSON:API

JSON:API is a standard for a lot more than just errors, it attempts to help with a lot of design choices for HTTP APIs, outlining the general format of requests and responses in JSON when working with HTTP APIs.

In general it labels itself an anti-bikeshedding tool, and this is pretty accurate. HTTP API developers often feel like there are infinite possibilities, which can lead to a lot of discussions and arguments, so using implementations like JSON:API can get folks on the same page.

The following is an excerpt from the JSON:API standard at time of writing.

An error object MAY have the following members:

- id — A unique identifier for this particular occurrence of the problem.

- href — A URI that MAY yield further details about this particular occurrence of the problem.

- status — The HTTP status code applicable to this problem, expressed as a string value.

- code — An application-specific error code, expressed as a string value.

- title — A short, human-readable summary of the problem. It SHOULD NOT change from occurrence to occurrence of the problem, except for purposes of localization.

- detail — A human-readable explanation specific to this occurrence of the problem.

- links — Associated resources, which can be dereferenced from the request document.

- path — The relative path to the relevant attribute within the associated resource(s). Only appropriate for problems that apply to a single resource or type of resource.

-— JSON:API

Pretty familiar stuff here! Whilst RFC 7807 has an interface that suggests one error object be returned with multiple problems provided using extra properties, JSON:API errors are an array of error objects.

HTTP/1.1 422 Unprocessable Entity

Content-Type: application/vnd.api+json

{

"errors": [

{

"source": { "pointer": "/data/attributes/firstName" },

"title": "Invalid Attribute",

"detail": "First name must contain at least three characters."

},

{

"source": { "pointer": "/data/attributes/firstName" },

"title": "Invalid Attribute",

"detail": "First name must contain an emoji."

}

]

}

That "pointer" is a JSON Pointer (RFC

6901), and can be used to point to the

specific location in the HTTP request body that failed.

This is great for client developers who have a UI. They probably already have

some logic which maps their form inputs to request data, so if they use that

pointer they can trace the error back to a form input, and show custom

validation errors even if they had not built that validation into their

frontend.

Note: Clients love copying validation rules into their applications and

that leads to all sorts of problems. Provide them with an alternative using

JSON Schema client-side

validation.

There are a lot of implementations for

JSON:API. To be frank, some are better

than others, by which I mean some are amazing and some are truly terrible. Check

a few out.

Should You Use a Standard?

RFC 7807 was only released as a final RFC in 2016, and JSON:API is also fairly

recent in the grand schema of the Internet. As such there are not many popular

APIs using them. This is a common stalemate scenario where people do not

implement standards until they see buy-in from a majority of the API community,

or wait for a large company to champion it, and seeing as everyone is waiting

for everyone else to go first nobody does anything. The end result of this

stalemate is that most people roll their own solutions, making a standard less

popular, and the vicious cycle continues.

Many large companies are able to ignore these standards because they can create

their own effective internal standards, and have enough people around with

enough experience to avoid a lot of the common problems around.

Smaller teams that are not in this privileged position, can benefit from

differing to standards written by people who have more context on the task at

hand. If you are Facebook then certainly roll your own error format, but if you

are not then RFC 7807 will point you in the right direction, and implementations

make it easy.

200 OK and Error Code

HTTP 4XX or 5XX codes alert the client, monitoring systems, caching systems, and

all sorts of other network components that something bad happened.

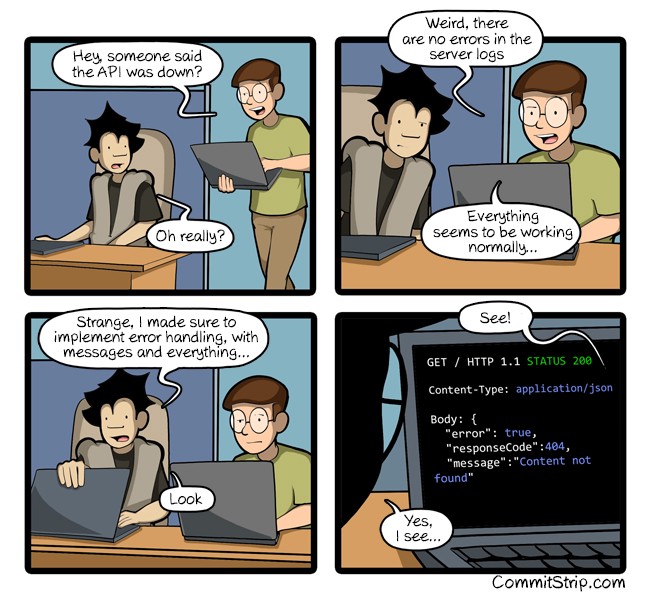

The folks over at CommitStrip.com know what’s up.

If you return an HTTP status code of 200 with an error code, then Chuck Norris

will roundhouse your door in, destroy your computer, instantly 35-pass wipe your

backups, cancel your Dropbox account, and block you from GitHub.

It is the hidden error. HTTP-based monitoring systems do not know about your

arbitrary { success : false } conventions and so do not report errors.

HTTP network caching will cache your errors because you are recording them as

not errors.

Do. Not. Use. 200. For. Errors. Ok?!

GraphQL

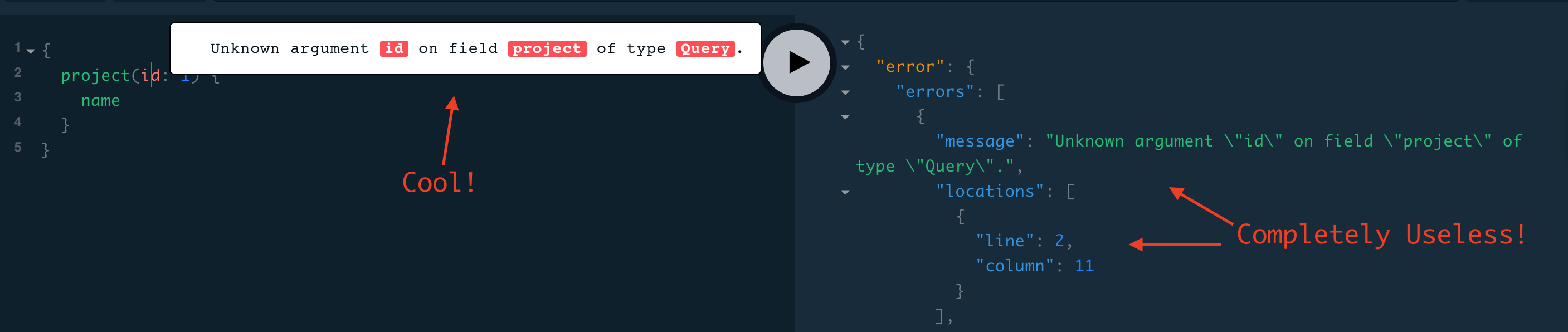

GraphQL has an error object format defined, so in theory no choice should need

to go into selecting one. It has a message and a location, the location being

useful for GraphIQL and other visual query tools to help show which line the

error was on.

There is also a path property made available in some error responses:

"path": [

"name"

],

At first this may appear to be similar to the JSON:API pointer (JSON Pointer) approach, but is actually considerably more complex.

If an error can be associated to a particular field in the GraphQL result, it must contain an entry with the key path that details the path of the response field which experienced the error. This allows clients to identify whether a null result is intentional or caused by a runtime error.

This field should be a list of path segments starting at the root of the response and ending with the field associated with the error. Path segments that represent fields should be strings, and path segments that represent list indices should be 0-indexed integers. If the error happens in an aliased field, the path to the error should use the aliased name, since it represents a path in the response, not in the query.

For example, if fetching one of the friends’ names fails in the following query:

{ hero(episode: $episode) { name heroFriends: friends { id name } } }The response might look like:

{ "errors": [ { "message": "Name for character with ID 1002 could not be fetched.", "locations": [ { "line": 6, "column": 7 } ], "path": [ "hero", "heroFriends", 1, "name" ] } ], "data": { "hero": { "name": "R2-D2", "heroFriends": [ { "id": "1000", "name": "Luke Skywalker" }, { "id": "1002", "name": null }, { "id": "1003", "name": "Leia Organa" } ] } } }-— Lee Byron, graphql-spec

As you might have noticed here, GraphQL has an interesting spin on errors. With

most HTTP APIs you are either trying to do something and succeed, or you fail,

and it is usually rather binary.

**Note: **An exception to that rule might be trying to fetch a collection of

things, searching, etc. and getting an empty result, but that is not an error,

that is a fetch returning an empty result.

GraphQL has a different take, and it tries to provide as much data back even

when a request contained incorrectness. It usually seems more like GraphQL

considers errors to be merely warnings, which is why you can have data and also

have errors, and that not be an issue.

When trying to work out where people should put their own errors, there are a lot of disparate instructions. Some folks saying things like:

If the viewer should see the error, include the error as a field in the

response payload. For example, if someone uses an expired invitation token and

you want to tell them the token expired, your server shouldn’t throw an error

during resolution. It should return its normal payload that includes the error

field. It can be as simple as a string or as complicated as you desire:return { error: { id: '123', type: 'expiredToken', subType: 'expiredInvitationToken', message: 'The invitation has expired, please request a new one', title: 'Expired invitation', helpText: 'https://yoursite.co/expired-invitation-token', language: 'en-US' } }

This is back to creating custom error formats, despite GraphQL having one

bundled...

Once again, GraphQL is so vague on a particular topic that it is not very

helpful, and the vendors have to step in. Apollo has extension based tooling

for errors

which can help you, but the usual concerns about vendor lockin, $$$ and having

extension-riddled APIs apply.

gRPC

gRPC does not care about how you do errors, do what you want. The official

documentation for gRPC Core has written down some pre-defined error

codes, but you can invent

your own too.

The official documentation pushes readers towards

https://avi.im/grpc-errors/, which is a convenient

set of SDKs for most of the programming languages gRPC is implemented in. The

code helps API developers use the status codes defined in gRPC Core, and add

their own text too.

All this and more in Build APIs You Won't Hate: Second

Edition, currently available

for pre-order with the early chapters available for download.